Starting a game studio can be one of the most exciting journeys in your creative career, but it also comes with real challenges. From managing people and timelines to balancing creativity with business strategy, every decision matters.

One of the most valuable lessons I’ve learned over the years is this: Start small, stay focused, and scale gradually.

A small and efficient team allows you to maintain creative control, minimize risk, and move faster. It’s not about having more people, it’s about having the right people at the right time.

Here’s a structured guide to help you build and run your own small game studio effectively.

1️⃣ Define Your Core Team Structure

Before you start hiring, it’s important to understand that every game studio operates around two types of team members: Primary and Secondary.

🎯 Primary Members

These are your core team members, the backbone of your studio. They are involved in every stage of game development, from concept to post-launch.

Typically, they include:

- Game Designer – Defines the concept, mechanics, and player experience.

- Game Programmer – Translates ideas into functional, playable systems.

- Project Manager – Keeps the production organized, tracks timelines, and manages priorities.

In the beginning, you only need one person per role. Keeping the team small ensures decisions are quick, communication is clear, and responsibilities are well defined.

Why are they called primary? Because their involvement is constant. Whether the game is in pre-production, testing, or release, these roles remain active.

2️⃣ Add Supporting Roles When Needed

🎨 Secondary Members

Secondary members are professionals who support production but are not required throughout the entire development cycle. These typically include:

- 2D or 3D Artists

- Graphic Designers

- Sound Designers or Composers

They play a critical role in the prototype and polishing phases, when visual and audio assets are developed. Once those assets are complete, their work usually pauses until new content or updates are needed.

That’s why for early stage studios, it’s best to hire secondary members as freelancers or temporary contractors. This approach keeps your budget flexible and ensures you only pay for what you need, when you need it.

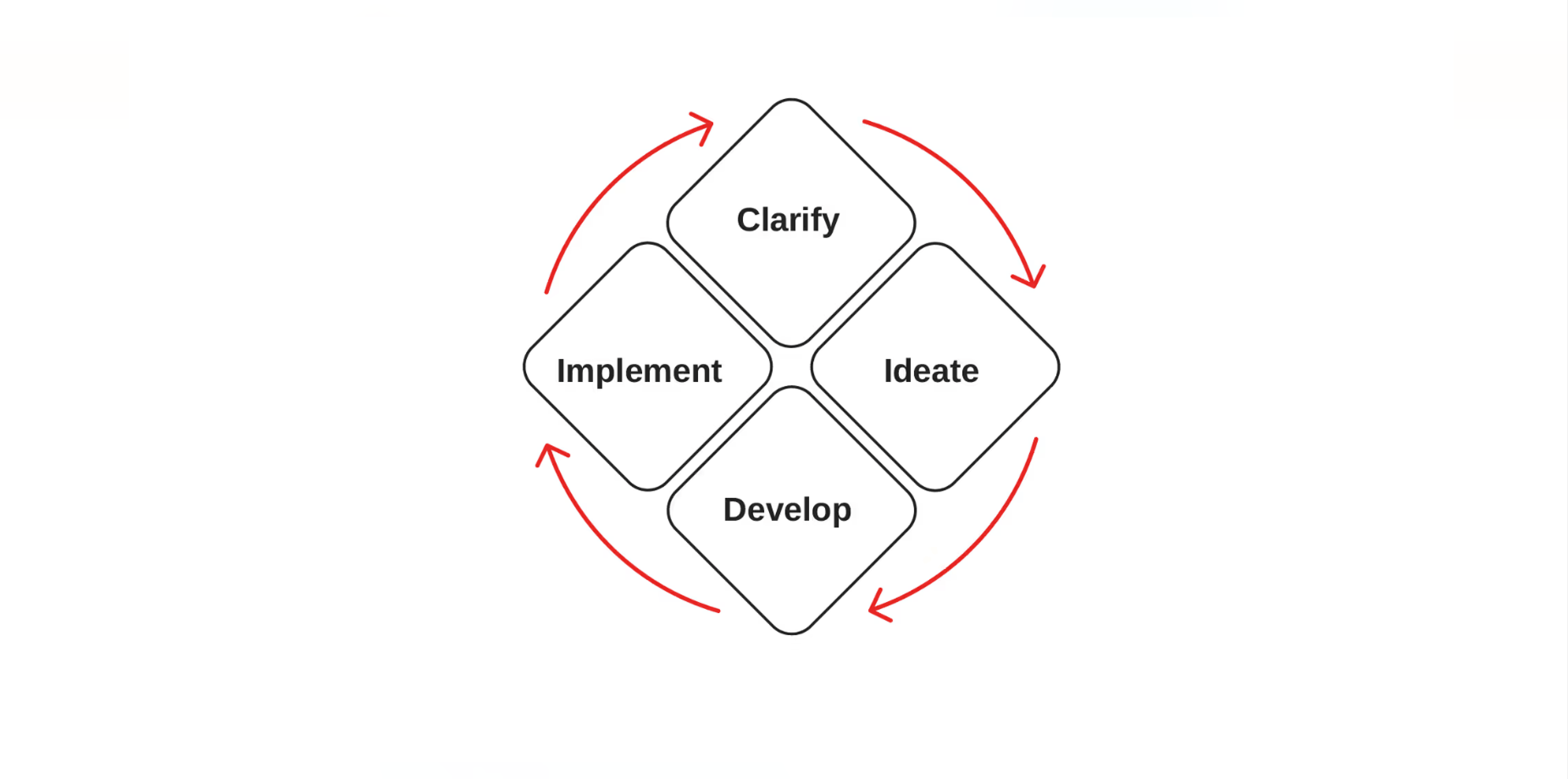

3️⃣ Focus on Coordination and the GDLC Framework

One of the most underestimated success factors in small studios is coordination, especially between the Game Designer and Project Manager.

Together, they should manage three key aspects:

- Timeline accuracy – ensuring milestones are realistic and achievable.

- Resource management – balancing scope with available manpower.

- Game Development Life Cycle (GDLC) – following a structured process from concept to post-launch.

Understanding and implementing the GDLC framework helps maintain development discipline. It ensures your project moves through well defined stages, pre-production, production, testing, launch, and post-launch iteration.

In my experience, studios that respect the GDLC process tend to see stronger outcomes within the first six months, both in production quality and team morale.

4️⃣ Scale Gradually as the Studio Grows

Once your first game is published and starts gaining players, you’ll likely need to release updates or additional content. This is the perfect moment to start growing your team strategically.

Here’s how you can scale responsibly:

- Gradually move key Secondary Members (like artists) into Primary positions.

- Recruit junior artists or designers on a trial basis before making them full-time.

- Align every hiring decision with your revenue growth and content roadmap.

The rule of thumb is simple: Grow based on demand, not on assumption.

Expanding too early can lead to unnecessary expenses and slower production. Instead, grow your studio organically, as your game’s needs and revenue justify it.

5️⃣ Apply and Learn from Real Projects

Theory is valuable, but experience is the best teacher.

When I graduated with a degree in Game Design, I applied this approach to form a small team with my classmates and former project collaborators. Our initial goal was simple: create portfolio projects to showcase our skills.

Not long after, we received our first paid project from an event organizer who needed a custom game for their event. For areas outside our expertise, I brought in secondary members, talented freelancers I had previously worked with on voluntary projects.

This mix of dedicated core members and flexible external support allowed us to deliver quality results, meet deadlines, and keep our studio sustainable.

It also gave us valuable experience in managing contracts, client communication, and production pipelines, all crucial skills for any studio founder.

🧭 Key Takeaways

Building a game studio doesn’t have to be overwhelming. With the right structure and mindset, even a small team can produce meaningful, successful projects.

Here are the key points to remember:

- ✅ Start small with a focused, core team.

- ✅ Hire flexibly, use freelancers for specialized work.

- ✅ Follow the GDLC to maintain production discipline.

- ✅ Scale gradually as your game and revenue grow.

- ✅ Build a network of reliable collaborators early on.

Ultimately, the goal isn’t just to make games, it’s to build a studio that can sustain creativity, adapt to change, and thrive long term.

📎 Related Article

For a real world case study of building a small game team from scratch, check out: