1. Overview

This 60 credit project represents the culmination of my final year Practical Project as a Game Design student at Teesside University, Middlesbrough (2010/2011). Drawing from over eight years of experience designing maps for Counter-Strike 1.6 and Counter-Strike: Source, I developed a fully playable, team based multiplayer level set in a realistic environment, the very campus I studied on.

This project was not only an academic requirement but also an opportunity to translate real world architecture into interactive game design using professional level tools.

2. Project Objective

The primary goal of the project was to design and implement a competitive multiplayer map for Counter-Strike: Source, showcasing my understanding of game level design principles. This included creating a balanced and immersive environment, optimizing the map for performance, and aligning the gameplay with Counter-Strike’s established mechanics. The project served as both a portfolio piece and a hands on learning experience that strengthened my technical and creative skills.

3. Idea

Imagine walking around your university campus and suddenly thinking,

“What if this place were a Counter-Strike map ?”

That’s exactly what happened to me during my final year as a Game Design student at Teesside University, Middlesbrough – UK. What began as a casual observation quickly evolved into the core of my final year Practical Project: designing and developing a fully playable multiplayer level set on my own campus.

This article walks you through the concept, research, design process, and lessons learned, a combination of creativity, technical execution, and passion for level design.

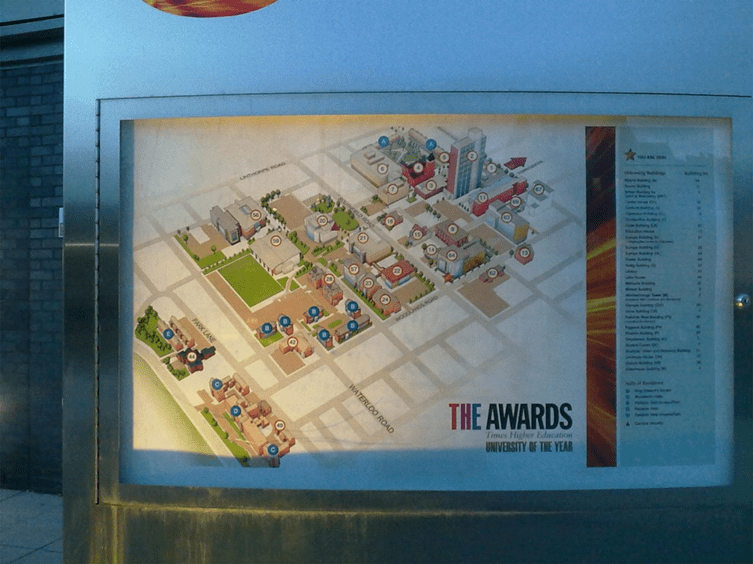

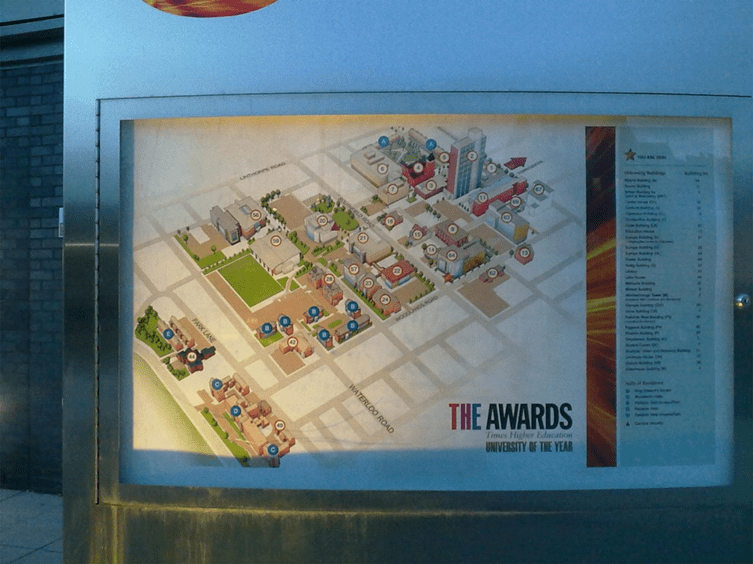

The idea took shape one day as I was leaving a lecture. Near the Athena Building, I noticed a large neon board displaying a 3D perspective map of the campus. The stylized rendering, combined with the structure of the surrounding buildings, sparked an instant “what if” moment.

I could clearly visualize routes, chokepoints, cover zones, and objective areas, all mapped to the real world environment I walked through daily. That moment of inspiration led me to pitch the concept to my supervisor. We both agreed: this would be a unique and ambitious final project.

From there, the challenge was to translate real world architecture into compelling level design for one of my all time favorite games, Counter-Strike: Source. The project aimed to blend realism with the tactical, fast paced gameplay that defines the Counter-Strike series, while applying everything I’d learned about competitive balance, navigation flow, optimization, and spatial storytelling.

This wasn’t just a student assignment, it was a personal milestone and a stepping stone into the professional world of level design.

4. Selected Game for the Project

The chosen game was Counter-Strike: Source (CS:S). The decision was based on several factors:

- I had spent years playing and designing for the game.

- Its editor, Valve Hammer Editor, is robust and familiar.

- The game’s community values custom maps, providing real world exposure.

- CS:S offers objective based gameplay that suits tactical level design, making it ideal for a project emphasizing balance and strategy.

5. Game Engine

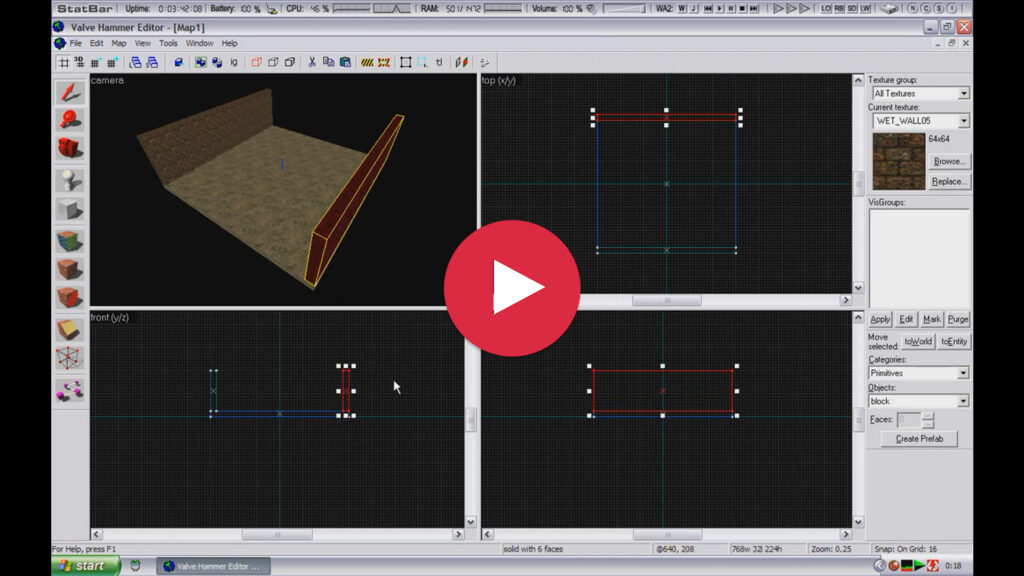

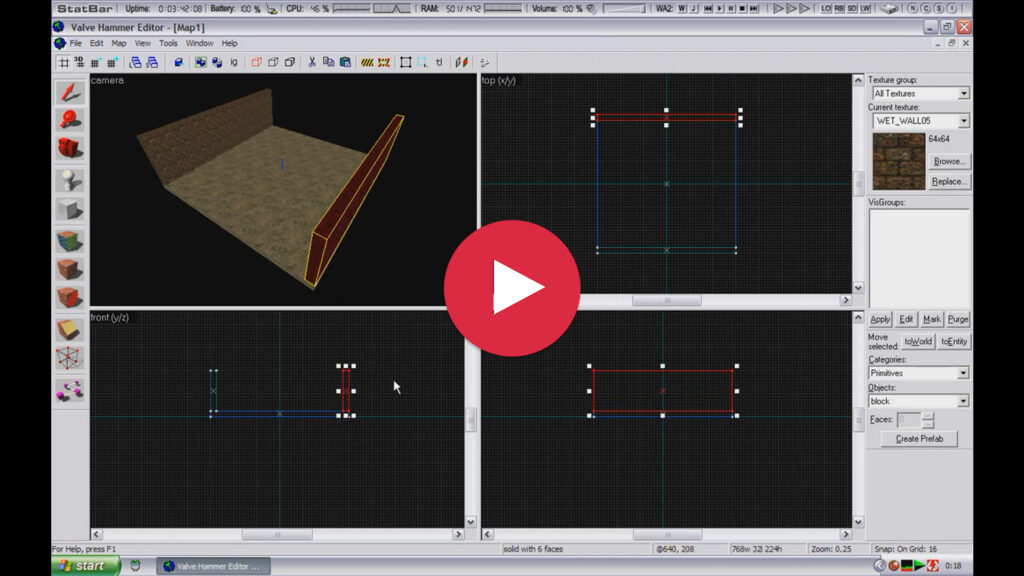

The project was developed using the Source Engine, through the Valve Hammer Editor (VHE). The Source Engine was selected due to its:

- Strong support for modding and custom content.

- Efficient rendering and asset integration pipeline.

- Personal familiarity and proven reliability over other tools I had tried.

- VHE allowed for rapid prototyping, accurate measurement tools, and fine control over environment setup, all crucial for building a detailed, real world inspired level.

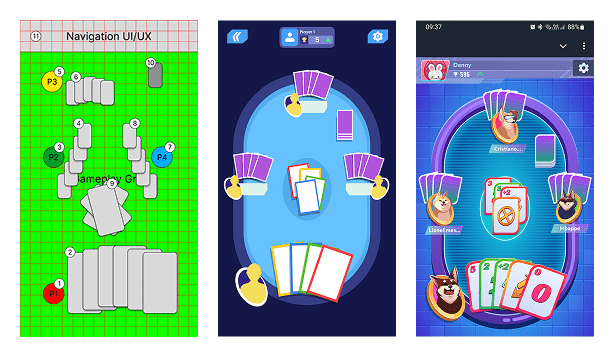

6. Designing the Level

Research & Preparation

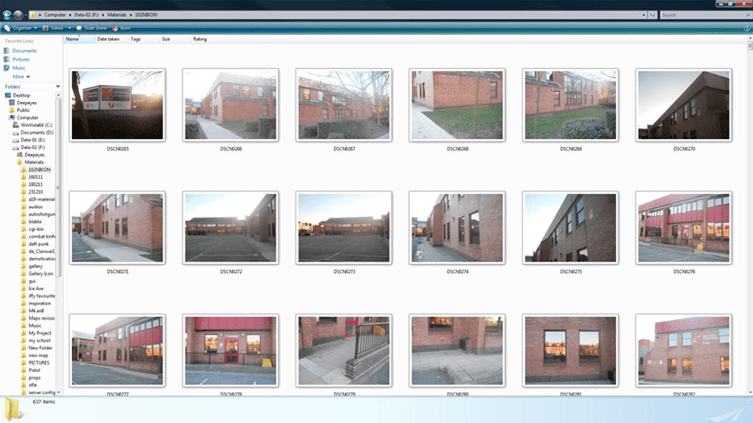

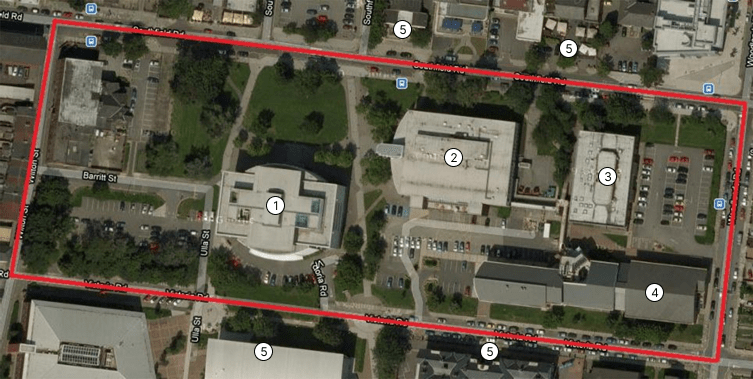

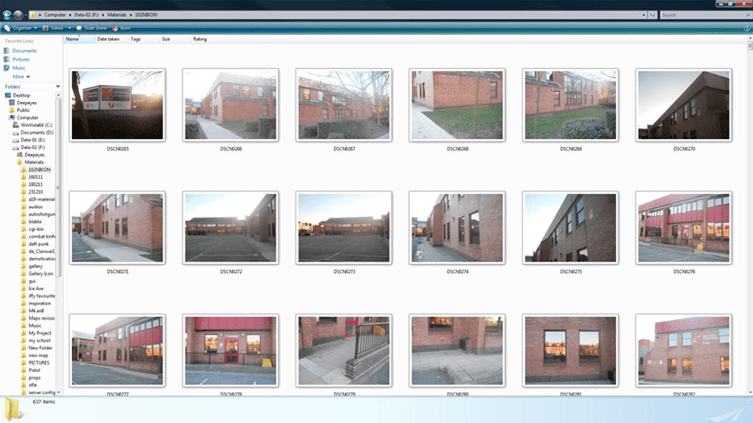

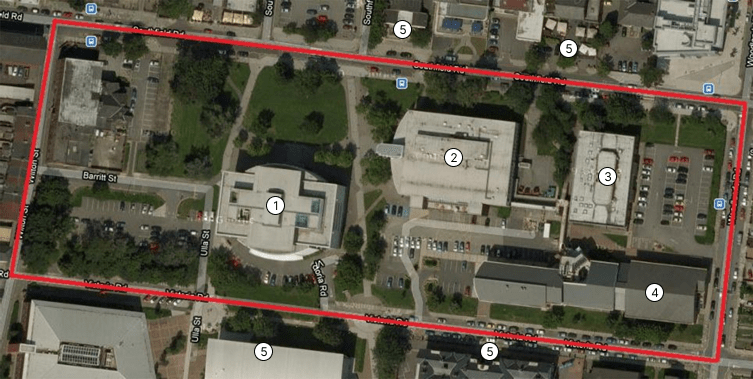

I began with site research, using Google Maps, on site photography, and the university’s official campus map. Because interior access was restricted, the entire map was built outdoors only, using visual assets such as windows, walls, and building exteriors for scale.

Building Index:

- Library

- Student Union building

- Grieg building

- Europa building

- Civilian houses

Concept Development

A top down 2D map was created to guide layout planning. Photos were taken under favorable weather conditions to gather visual references and estimate measurements (e.g., a friend was used for scale). The final map focused on three core buildings:

- Grieg Building

- Student Union

- Europa Building

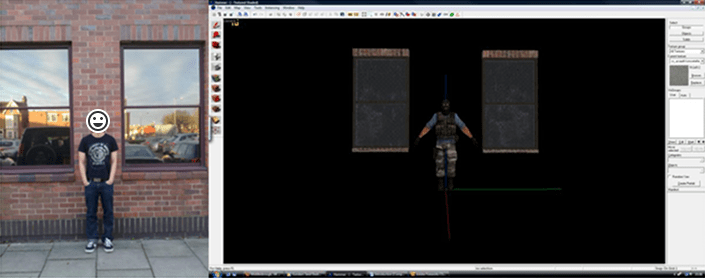

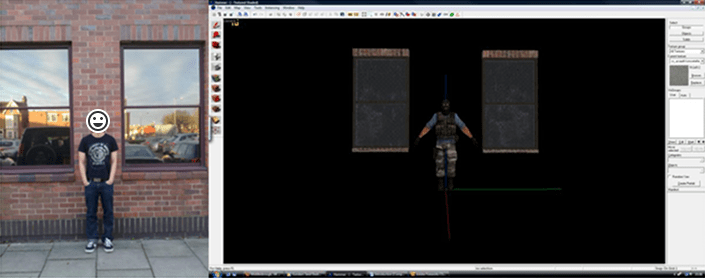

Measurements & Scaling

Accurate measurements were essential. Since I couldn’t access official blueprints, I used a practical modeling technique:

I asked a friend (approx. 175–180 cm tall) to stand between two windows of the Grieg Building. By comparing this scale with in game character models and using the windows as reference points, I created a proportional system.

From there, I measured:

- Building widths and heights

- Door and window dimensions

- Spacing between architectural features

- Estimated distances between buildings

This measurement method allowed me to scale the structures precisely inside the game editor, resulting in believable architecture that supported intuitive player movement and sightlines.

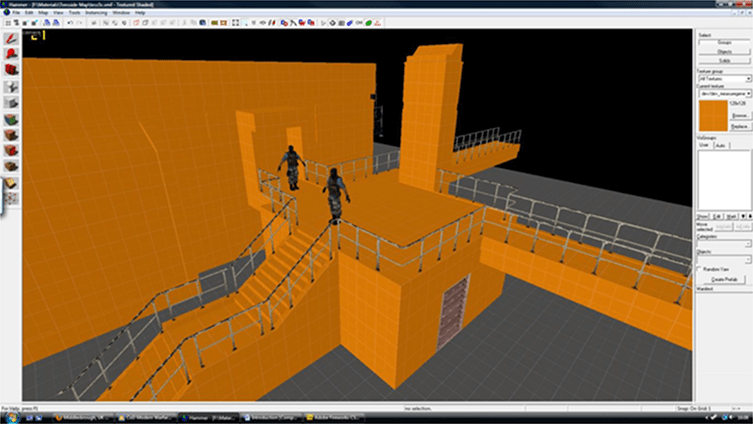

Technical Design

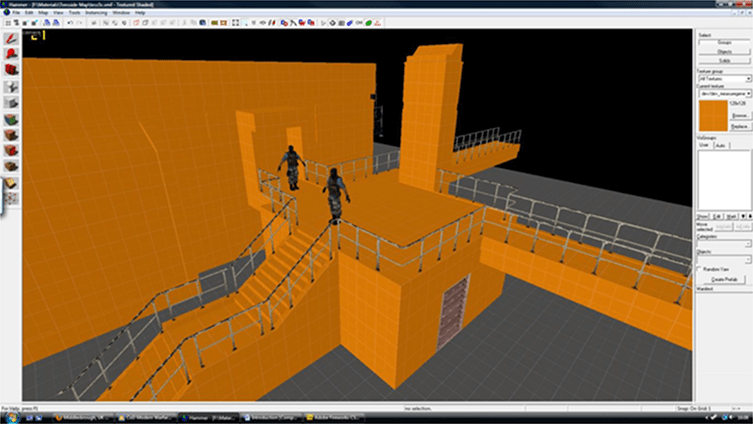

The Block Tool in the editor is primarily used to create basic geometric shapes such as arches, blocks, cylinders, spheres, spikes, tori, and wedges. Once a brush is placed, it can be easily manipulated stretched, resized, or reshaped directly within the editor, with no need for scripting or coding.

I modeled the level’s architecture while applying core level design principles such as player flow, sightlines, and cover. Key structural elements included:

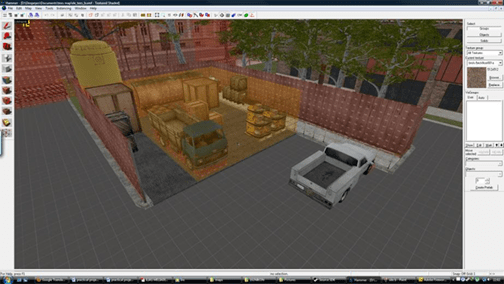

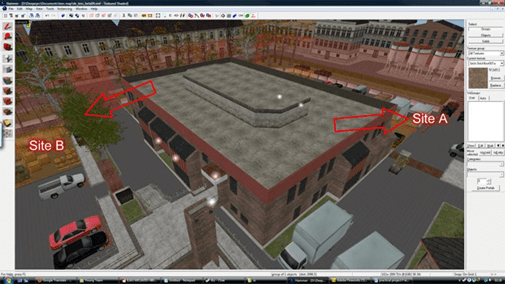

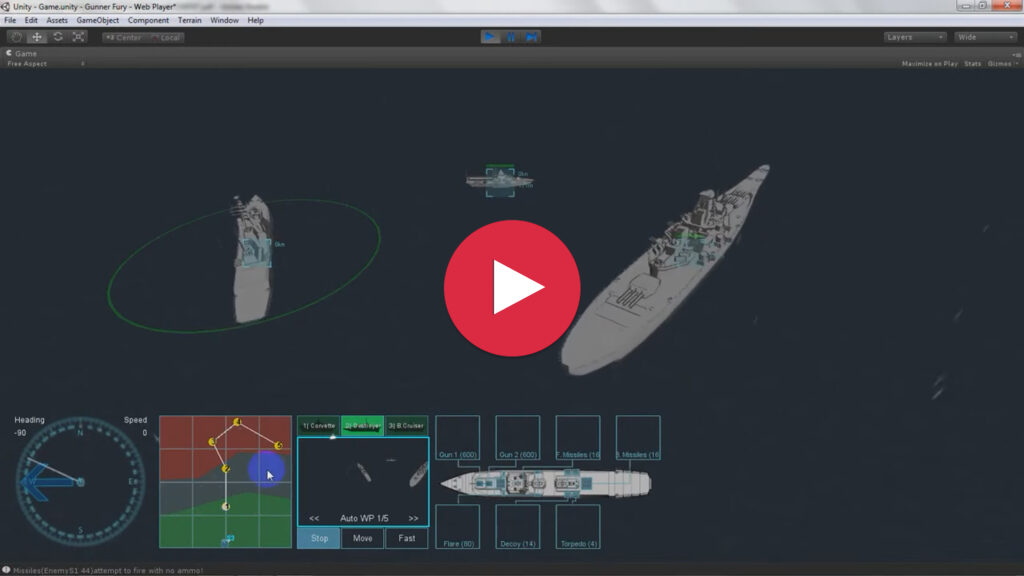

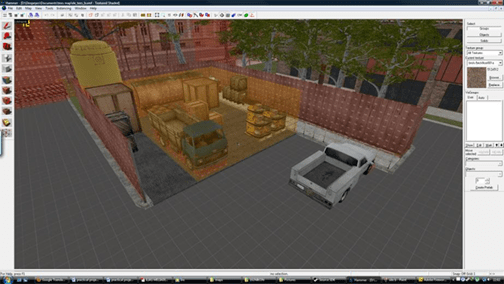

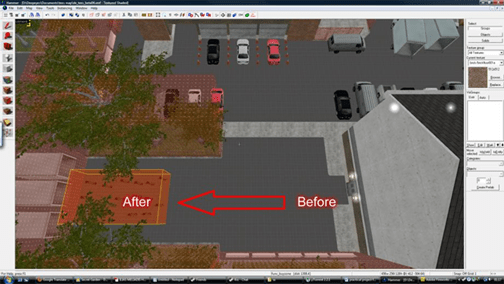

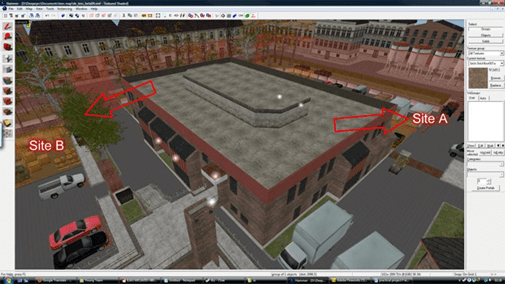

Bombsite A: The parking lot at the Grieg Building. It contains valuable crates/goods that need to be either protected or destroyed.

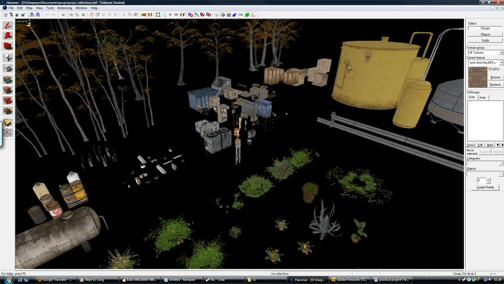

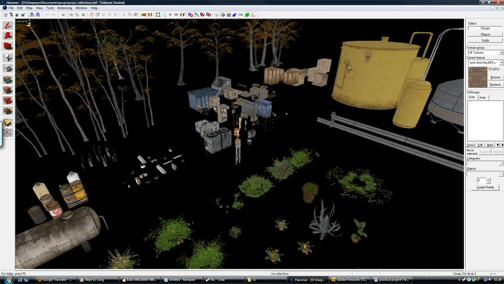

Bombsite B: The loading bay at the back of the Student Union building. It consists of chemical tubes and toxic barrels. Some of the barrels can explode if hit by bullets or a knife.

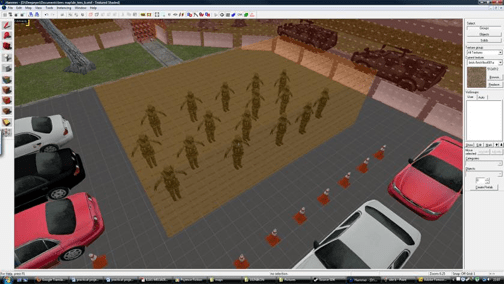

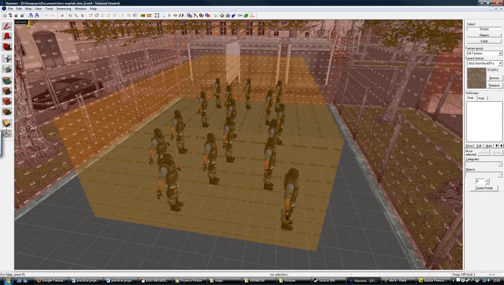

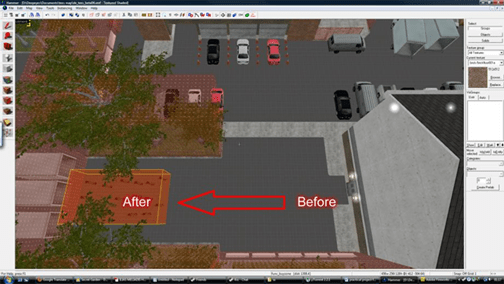

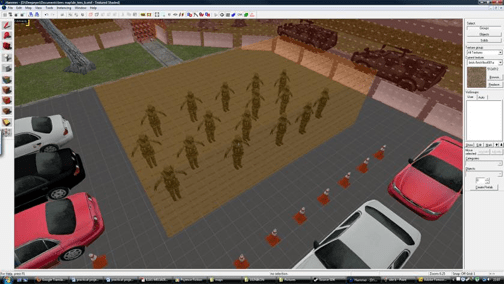

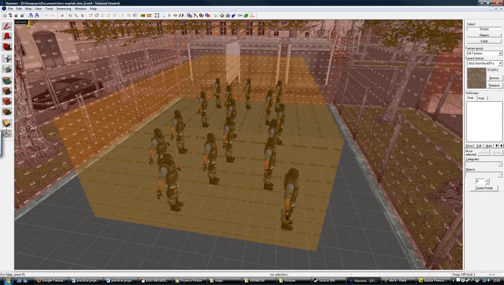

Counter-Terrorist spawn point: Located in the parking lot near the Grieg building. It consists of 16 available slots. The yellow box surrounding the players is a trigger that serves as a buy zone for the Counter-Terrorist team only, meaning only Counter-Terrorist members can purchase weapons within this area.

Terrorist Spawn point: Located near the end of the Europa building. It consists of 16 available slots. The yellow box surrounding the players is a trigger that serves as a buy zone for the Terrorist team only, meaning only Terrorist members can purchase weapons within this area.

Fast Paced Gameplay: Despite the map being quite large (from a character’s perspective), the author found that the map is easy to explore. The player can reach the main mission objective without needing to reroute. The entire layout is very easy to memorize, even for a beginner player. The invisible barriers around the map will keep players within the boundaries.

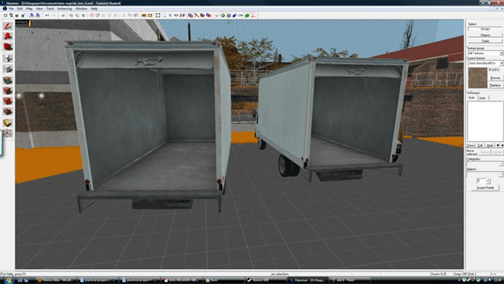

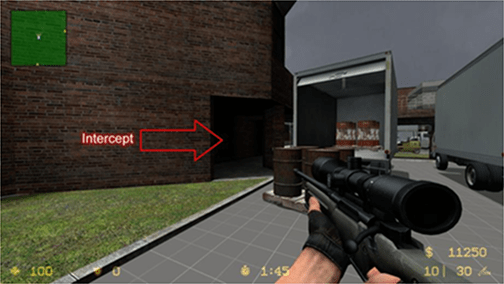

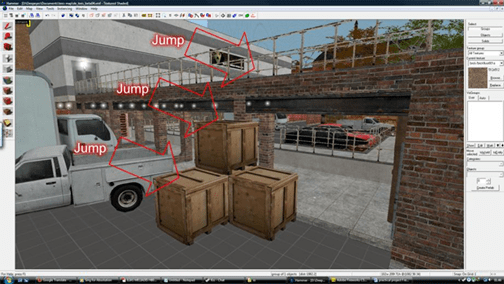

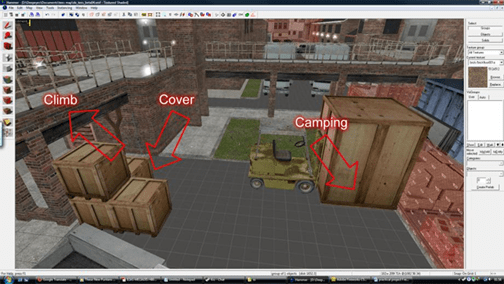

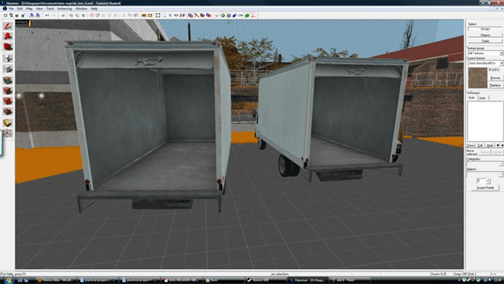

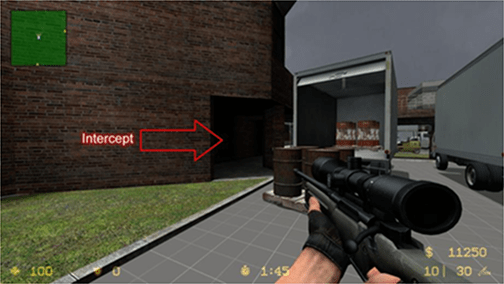

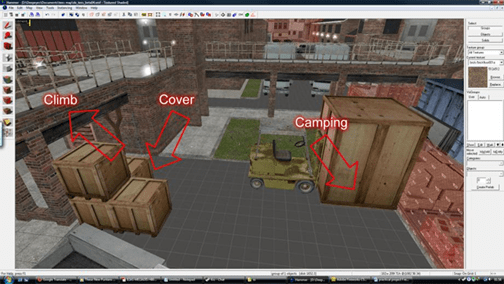

Element of Surprise: By adding plenty of stationary trucks, players can jump in to hide. Some of the trucks are equipped with a pair of explosive barrels in their cargo area. These barrels will explode if hit by a bullet, killing anyone standing too close to them. To fill the gaps within the map, this problem can be solved by adding a variety of stationary vehicles and crates of different sizes. Players can use them for cover if spotted by the enemy or to climb to higher ground. The trees on the map also provide cover, as they contain collision detection that blocks both visual contact and bullets.

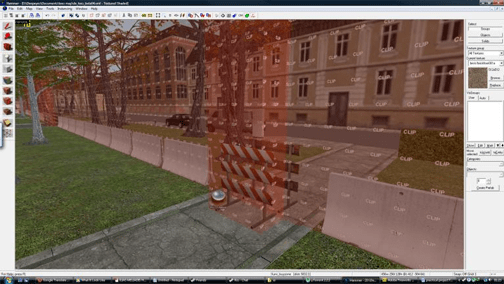

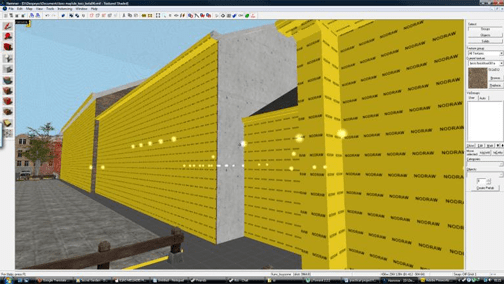

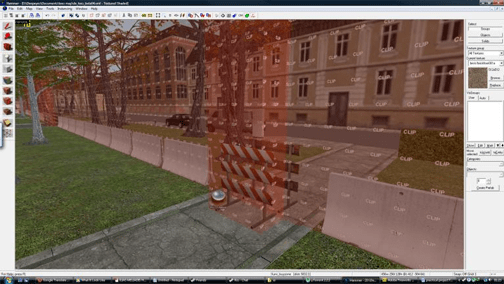

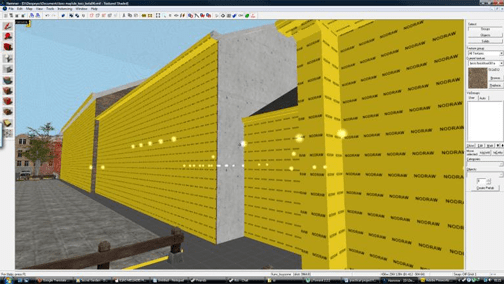

Invisible Barriers: Surrounding the map is marked with the ‘clip’ texture, to keep the player within the designated mission objective area.

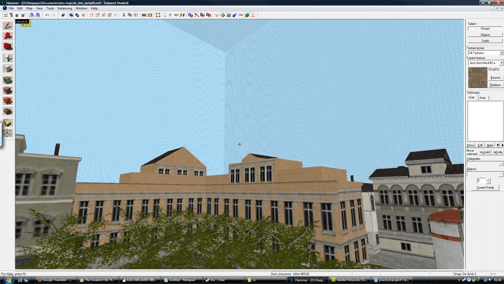

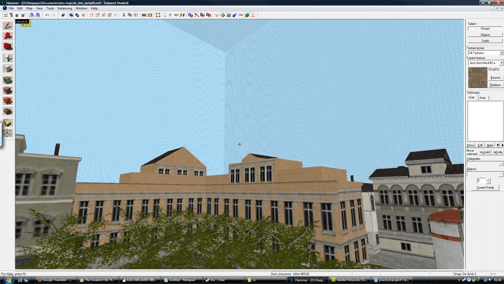

Sky Box: The sky surrounding the map is made from a blue texture intended to represent a specific theme, which is a combination of a set of images.

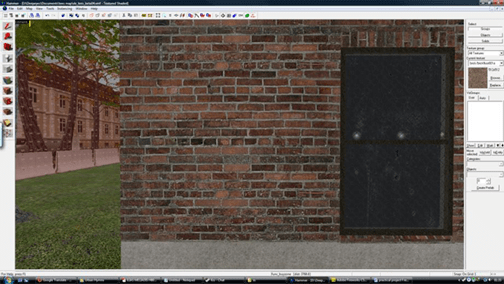

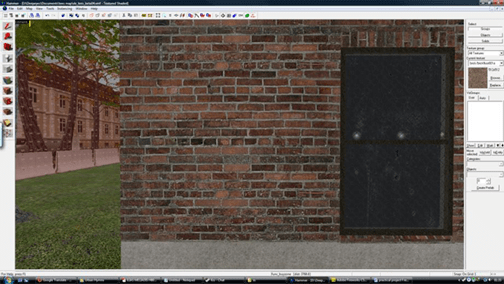

Textures: Some of the textures in the map represent the actual materials of the structures, such as red bricks.

Prop Distribution: List of props that currently are in use in general, 8 types of Vehicles, 7 types of Trees, 2 types of bushes, 5 types of Crates, 2 types of Barricades, 4 types of Barrels, 5 types of Tubes, 2 type of Fences and plenty of small items which work as additional details.

The layout emphasized:

- Simplicity for quick memorization

- Multiple approach paths to key objectives

- Strategic use of real world terrain and cover

Each asset was scaled based on real world references, ensuring a believable environment that remained easy to navigate.

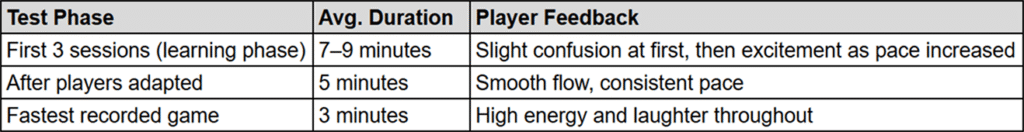

7. Testing the Level

Map Compilation Process:

Once the layout, gameplay entities, and visual design were complete, the level was compiled using the Valve Hammer Editor’s compile tools. The process included:

- VBSP: Converts geometry and brushes into the in game world

- VVIS: Calculates visibility data for optimized rendering

- VRAD: Processes lighting and shadows

- The resulting

.bsp file was then tested in Counter-Strike: Source for playability, performance, and bug checking

The computer used to compile the map:

- Operating System: Windows Vista Ultimate – Service Pack 2 – 64-bit Edition

- Processor: Intel Core 2 Quad Q6600 (4 cores) @ 2.40 GHz

- Memory (RAM): Corsair XMS2 DHX DDR2, 2 GB x2 (Dual Channel)

- Hard Drives: Seagate 80 GB Seagate 1 TB x2

- Graphics Card: XFX Nvidia GeForce GTX 260, 896 MB

- Motherboard: Gigabyte X48-DQ6

- Monitors: Acer X223HQ 21.5-inch x2

- Sound Card: Realtek AC’97

The map underwent several rounds of testing with bots in game. I conducted iterative play sessions to:

- Analyze movement flow

- Identify overpowered positions

- Check visibility and collision issues

- Evaluate time to engagement between teams

Note: The compilation was run using the default lighting configuration. The author decided not to activate the HDR feature, as the map is still in the testing phase. Full lighting features will be available in the final version, which is currently under development.

Later, I invited friends to playtest and gather human feedback. Through these sessions, I gained valuable insights into map balance, spawn placement, and visual readability.

8. Improving the Gameplay

Based on testing and player feedback, I made multiple refinements:

Replaced fences with vehicles: To open up flanking opportunities and improve gameplay fluidity.

Added more Trees: To improve aesthetics and additional protection for players.

Adjusted spawn distances: To ensure fair timing to bomb sites for Terrorist Spawn Point.

Introduced Destructible Elements: Such as explosive barrels, to discourage camping and added dark zones for stealth and ambush tactics.

Disabled Roof Access: Access to the rooftops has been removed, especially for the Grieg building. If a counter-terrorist player managed to reach the roof, they would have the opportunity to observe both bomb sites and exploit this advantage to target terrorists attempting to plant the bomb.

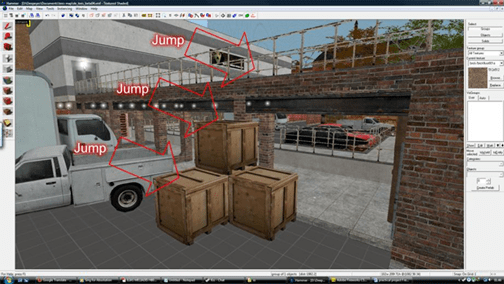

Introduce Shortcut: Players can climb on stacks of crates to bypass or escape from enemy barricades. For example, a player can jump onto a pile of crates to reach higher ground or access the bridge without using the stairs.

Added more props: Crates, trucks, barrels for cover and tactical flexibility, these improvements turned a static environment into a dynamic and strategic gameplay space.

Optimized Performance: By using invisible walls, special textures (e.g., nodraw, clip, trigger) to reduce compile time and improve framerate.

9. Conclusion

This project was a highly rewarding journey that bridged academic learning with industry relevant practice. From concept to implementation, I applied core level design skills, technical understanding, and creative decision making. The map not only received positive feedback from play-testers but was even picked up by three public servers (two in France and one in the USA).

Download the Map from the following link – Proton Drive