Creativity is one of the most valuable skills a game designer can have. Beyond simply generating new ideas, creativity is often the key to solving problems that arise during development whether they are design challenges, technical limitations, or gameplay imbalances.

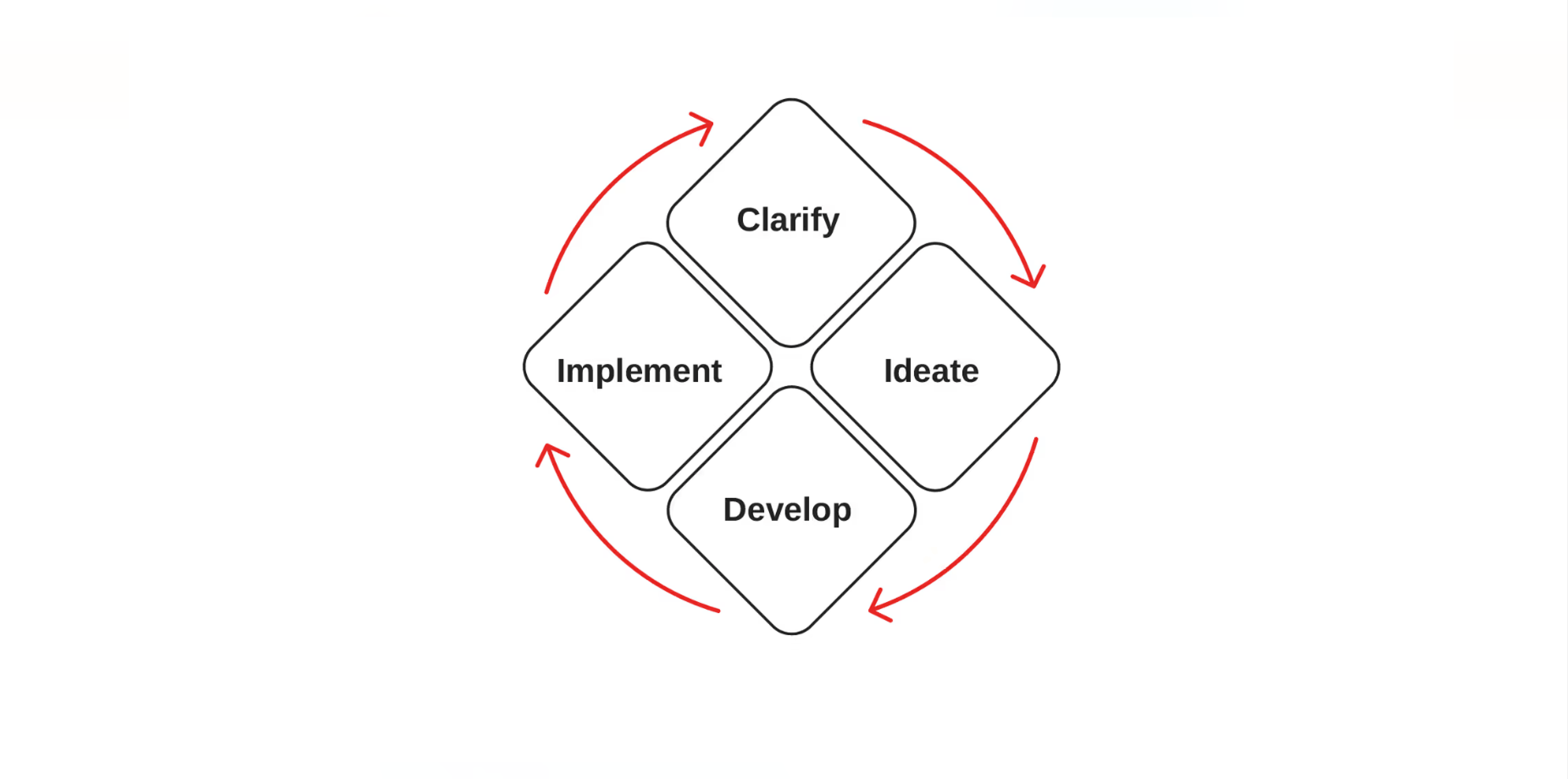

Understanding Creative Problem Solving (CPS)

Creative Problem Solving (CPS) is a structured way of using creativity to develop new ideas and solutions. The process often begins with clearly defining the problem. Without a clear understanding of the challenge, even the most innovative ideas may miss the target.

A creative solution in game design often shares certain characteristics:

- Using existing components: Reimagining or recombining assets, mechanics, or systems already present in the game.

- Turning problems into opportunities: Treating limitations (time, budget, technology) as a foundation for innovative solutions.

- Shifting perspectives: Looking at the challenge from the players viewpoint, a competitors design approach, or even a completely different genre.

Real World Case Studies of Creative Solutions

Case Study 1: The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild – Weapon Durability

- Problem: In open world RPGs, players often stick to a single powerful weapon once they find it, which reduces gameplay variety.

- Constraint: Nintendo wanted a system that encouraged experimentation without overwhelming players with unnecessary complexity.

- Solution: They introduced weapon durability, where weapons eventually break. This mechanic forced players to constantly rotate weapons, experiment with new combat styles, and use the environment creatively.

- Result: What could have been a frustration turned into a driver of exploration and variety, ensuring that combat stayed dynamic throughout the entire game.

Case Study 2: Portal – Depth from a Single Mechanic

- Problem: Puzzle games often struggle with either being too simplistic or too complex for players to enjoy.

- Constraint: Valve wanted a game that was intuitive but deep, while keeping mechanics minimal.

- Solution: They designed the Portal Gun, a tool that creates two connected portals. Instead of adding more tools, the team focused on recombining this single mechanic in increasingly clever ways.

- Result: Portal became a masterclass in design elegance, showing how constraints can lead to surprising depth and replayability.

Case Study 3: Minecraft – Building Survival from Blocks

- Problem: Minecraft originally started as a block building sandbox, but needed more depth to sustain long term engagement.

- Constraint: Mojang had a simple voxel system and limited resources for complex assets.

- Solution: They layered survival mechanics (hunger, health, monsters, crafting) directly into the block based world. Instead of creating entirely new systems, they extended the core building mechanic into survival gameplay.

- Result: This simple addition transformed Minecraft from a creative tool into a genre defining survival experience, massively expanding its player base.

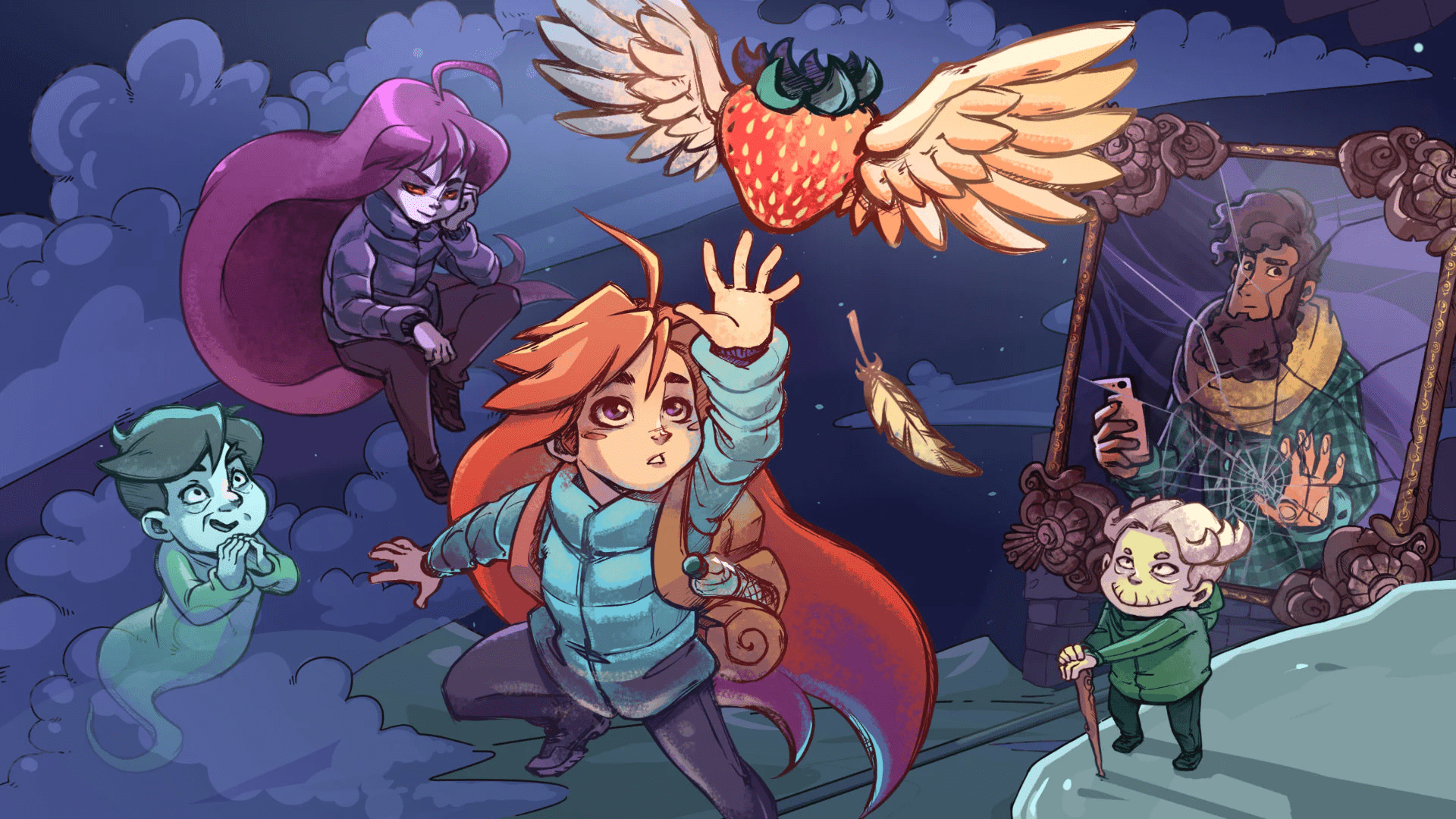

Case Study 4: Celeste – Framing Difficulty as Growth

- Problem: Platformers are often criticized for being too punishing, which can alienate players.

- Constraint: The developers wanted to keep Celeste challenging while making it emotionally accessible to a wider audience.

- Solution: They tied the narrative to the challenge, climbing the mountain became a metaphor for overcoming personal struggles. They also included optional assist features, such as slowing down time or skipping difficult sections, without diluting the core difficulty.

- Result: Celeste turned frustration into empowerment. The challenge felt meaningful, and the optional tools made the game approachable while preserving its integrity.

Case Study 5: Hollow Knight – Depth on a Budget

- Problem: A small indie team wanted to create a vast Metroidvania world with rich atmosphere.

- Constraint: Limited budget and team size meant they couldn’t rely on flashy 3D graphics or a massive content pipeline.

- Solution: Team Cherry adopted minimalist, hand drawn 2D art and designed layered, interconnected maps. Clever use of lighting, sound, and environmental storytelling gave the illusion of scale far beyond their resources.

- Result: Hollow Knight became a critically acclaimed Metroidvania, praised for its depth and atmosphere, proving that clever design can outweigh budget limitations.

Case Study 6: Undertale – Morality in Combat

- Problem: Traditional RPG combat can feel repetitive and disconnected from story themes.

- Constraint: Solo developer Toby Fox had limited time and resources to create a complex battle system.

- Solution: Instead of building complexity into mechanics, he added a moral choice system, players could fight or spare enemies, with consequences that shaped the story.

- Result: Undertale created emotional depth with minimal mechanics, turning a standard RPG loop into a powerful storytelling device.

Case Study 7: Papers, Please – Narrative Through Mundanity

- Problem: How do you create tension and emotional engagement with simple gameplay?

- Constraint: The developer, Lucas Pope, wanted to simulate bureaucracy without high end graphics or combat systems.

- Solution: The game cast players as a border inspector, where stamping documents and making small choices became the core mechanics. By tying these mundane tasks to moral dilemmas, the game created emotional weight.

- Result: Papers, Please delivered one of the most immersive dystopian experiences in gaming, without relying on traditional gameplay tropes.

Case Study 8: Among Us – Low Cost Social Gameplay

- Problem: With a small team and budget, InnerSloth needed to design a fun, repeatable game loop.

- Constraint: They couldn’t compete with AAA graphics or large scale systems.

- Solution: They focused on social deduction, a mechanic that required minimal assets but maximum player interaction. The tension came from communication, deception, and group dynamics rather than in game systems.

- Result: Among Us became a viral global hit, proving that strong social design can outperform technical polish.

Techniques to Support Creativity

Coming up with ideas, especially innovative ones, can be supported by proven techniques such as:

- Brainstorming & Mind Mapping: Rapidly generating ideas and visually connecting them.

- Scamper Method: Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, Reverse.

- Prototyping: Testing small, quick versions of mechanics to validate new approaches.

- Cross Genre Inspiration: Borrowing solutions from other genres or even outside gaming.

Conclusion

Creative problem solving is not just about being imaginative, its about applying creativity to practical challenges. By studying how both AAA and indie developers have turned problems and constraints into strengths, game designers can learn how to elevate gameplay, improve product quality, and transform obstacles into opportunities.

The best creative solutions often come not from unlimited freedom, but from embracing limitations, and rethinking them as opportunities to innovate.